What will the future of plastics be about?

The world of plastics is changing as traditionally the manufacturing of plastics has been based on oil refining side streams. Our expert Mikko Koivuniemi, Business & Technology Development Manager, shares his insights about how we at Fortum see the future of plastics recycling

Over the years, the petrochemical industry has become one of the most significant global industries. Oil states control the liquid fuel markets and energy production through their natural gas reserves. A well-oiled petrochemical industry engine has been created in which good use is made of all refinery derivatives. A small share of the crude oil that gets refined is used as raw material for plastics. European plastics production in particular leans heavily on petroleum naphta, which is mainly used to produce ethylene and propylene, which are among the most important raw materials for plastics.

But there’s trouble with the engine. As environmental awareness increases, the demand for fossil raw materials is declining, and transportation is electrifying as well. The demand for liquid fuels used in transportation is estimated to fall by one third from the predicted peak in 2027 by 2050. This will create a significant optimisation problem for refineries, because the distillation of crude oil always produces certain fractions that need to be put into use. The picture below shows a typical production breakdown of crude oil, in which approximately 80% of the production is petrol, diesel and jet fuel. Less than 10% ends up in plastics and other chemical industry products. However, the production cannot be adjusted to a great extent to significantly reduce liquid fuels and increase the share of feedstock for chemical uses.

The above picture shoes a typical production breakdown of crude oil, in which approximately 80% of the production is petrol, diesel and jet fuel. Less than 10% ends up in plastics and other chemical industry products. However, the production cannot be adjusted to a great extent to significantly reduce liquid fuels and increase the share of feedstock for chemical uses.

Additionally, governments seek to limit emissions even more than before to support environmental targets. In its study, Bloomberg has estimated that decarbonising the plastics industry will require investments of $759 billion by 2050 from the industry – on top of the usual capacity investments. Although the number is big, it is merely one per cent of what it will cost to make the global energy industry carbon neutral.

Alternative means for plastic production?

The carbon neutrality of plastics is a complex and capital-intensive challenge. In Europe, the alternative naphta needed in plastics production can be obtained from chemical recycling or bio-based production. With the latter, availability is a problem: the amounts remain very limited if significant harm to biodiversity is to be avoided.

The problem with chemical recycling has so far been poor yield and energy intensity. In addition, current technologies are very specific when it comes to feed materials. Pilot projects have been successfully carried out mainly with pure polyolefin fractions, the recycling of which can also be carried out mechanically.

Mechanical recycling is, in fact, currently the best operating model from the natural resources point of view, because the material balance in relation to energy consumption is fairly good. The downside is that the quality of mechanically recycled plastic is always poorer than that of virgin plastic, and use in, for example, food packaging is prohibited for the time being, excluding PET plastics.

Both chemical and mechanical recycling techniques require separate collection of materials, which is challenging if we want to reach recycling targets of above 50%. For consumers, recycling is entirely voluntary, and some materials are always thrown into mixed waste. In many European countries, including Finland, placing organic waste in a landfill is not allowed. Therefore, the only possible waste processing method is incineration into energy.

New technology and cooperation are needed

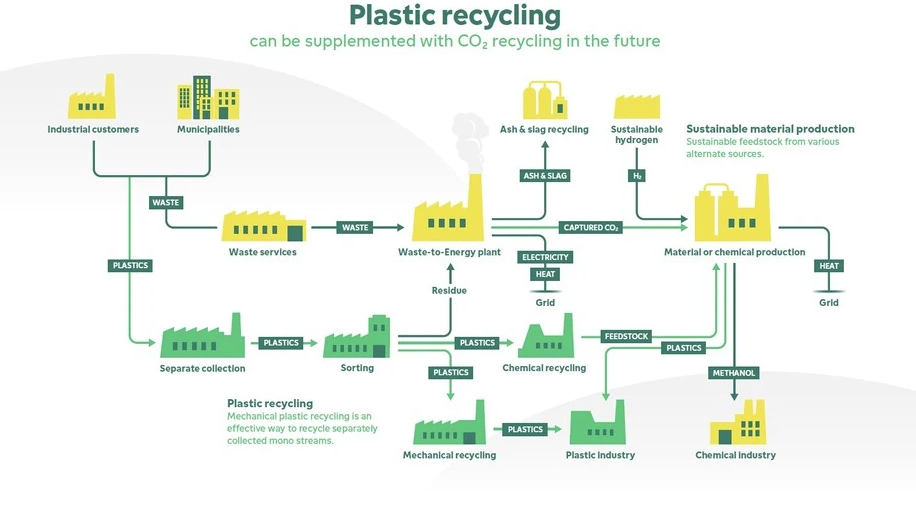

The most promising alternative for acquiring feedstock for the plastics industry is recycling the carbon captured from waste incineration plants. Developing this route still requires time and significant amounts of renewable energy. However, converting CO2 emissions into materials is the only way of combining efficient waste management, material efficiency and sufficient volumes. Picture below presents a vision of the future of the plastics industry.

In addition to alternative feedstocks, a technological change is needed in the polymer industry industry. The most important example of this is the electrification of cracker plants along with the shift from fossil fuels to renewable electricity.

In any case, the need for plastics continues to increase, and in many applications, plastic is the best alternative when the environmental load during useful life and lightness in relation to properties are taken into account.

There is no one correct solution. We need versatility in our toolbox, cooperation, and new technology. Regulation cannot lag behind development or – even worse – slow it down, as has now happened with carbon sequestration; capture and storage is recognised, but the legislation relating to carbon recycling is still very incomplete. In this, the key factor is not the years during which the carbon dioxide is stored, but more importantly, whether we are replacing fossil materials in packaging, for example.

Traditionally, the manufacturing of plastics has been based on oil refining side streams, which have been available in abundance and with a low price. CO2 emissions have hardly factored in in pricing. As we proceed towards alternative materials, emission costs will increase the cost level of raw materials permanently. This is something we have to accept in industry and trade, and ultimately among consumers. Furthermore, the price of CO2 emissions must be on a level that truly steers development towards alternative and novel solutions.

About plastic recycling at Fortum

Fortum recycles consumer plastic packaging mechanically in its plastics refinery plant in Riihimäki and uses it to produce Fortum Circo® plastic recyclate, which is an environmentally friendly and sustainable choice for raw material in the plastics industry. In addition, we are piloting CO2 capture at the waste incineration plant in Riihimäki, and our goal is to use the captured carbon as raw material in the production of new high-quality materials, such as plastic.

Source:

Fortum Blog, Press release, 2022-06.