U of T chemistry team advances to ‘close the carbon cycle’

Solar fuel breakthroughs showcased in new art exhibit in Vienna

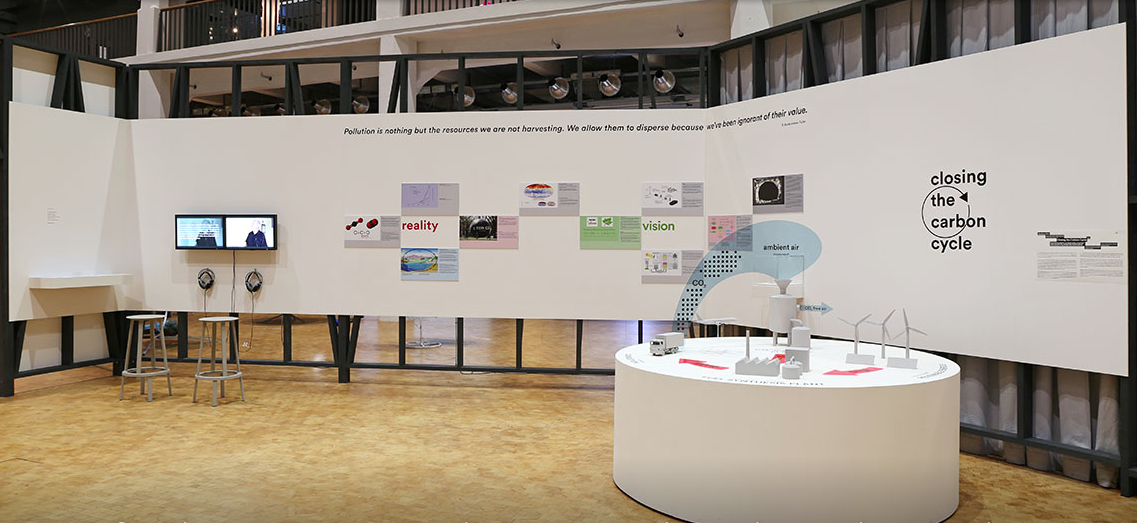

Closing the carbon cycle by U of T’s Geoffrey Ozin: The diorama will open in December at Austria’s Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (photo by Peter Weibel)

Making fuel out of polluted air, using it to power industry, and then taking the emissions from that industry back out of the air to create more fuel – it sounds too good to be true. But while there are a few hurdles to clear, a team led by University of Toronto’s Geoffrey Ozin of the department of chemistry in the Faculty of Arts & Science is getting closer to closing the carbon cycle.

“Carbon dioxide’s so frustrating because it’s the most stable molecule on the planet,” says University Professor Ozin of the climate pollutant that outlives soot, methane and hydrofluorocarbons by a long shot.

“That’s the problem. Anything you burn becomes CO2 and CO2 is really good at staying CO2,” says Ozin, who holds the Canada Research Chair of materials chemistry and nanochemistry.

For the last five years, Ozin has led a multidisciplinary team known as the U of T Solar Fuels Cluster on a quest to develop a process to convert atmospheric CO2 into a renewable fuel. Ozin says his plan for manufacturing the fuel would take as much carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere as burning the fuel would put back in.

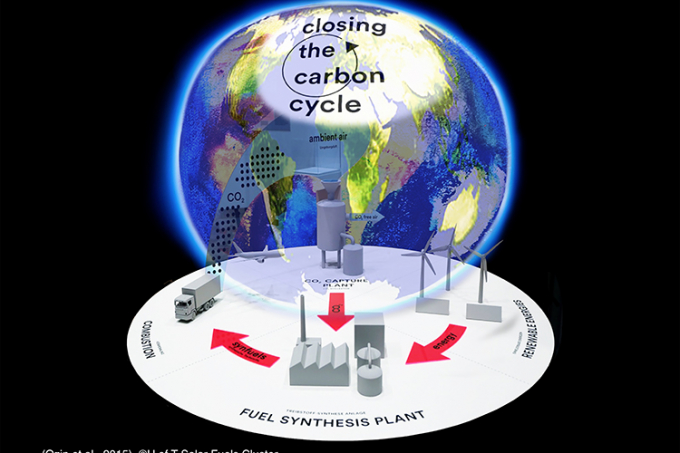

This photomontage unites the vision of a global CO2 utilization strategy with a fuel synthesis plant that enables closing the carbon cycle (image courtesy of Todd Siler and Geoffrey Ozin, Matthias Gommel and Peter Weibel, “GLOBALE: Exo-Evolution” exhibition at the Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe)

The team’s efforts have attracted the attention of major international corporations, and even inspired an exhibit about the process that’s been on display in Germany – a world leader in CO2 reclamation – and more recently in Austria.

The quest to make fuel out of waste carbon isn’t new, but Ozin and his team are the only ones using both the heat and light of the sun to convert CO2, hoping their process will be more efficient than anyone else’s.

Recently, Ozin’s work caught the eye of the director of the Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany, which specializes in multimedia exhibits at the confluence of art and science. The result was a vivid diorama depicting Ozin’s vision that has met with acclaim in Karlsruhe and will open in December at Austria’s Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna.

It is not the first time Ozin’s research has been immortalized in art. In 2011, American artist Todd Siler began creating multimetre-tall abstract sculptures of Ozin’s nano-structures, showing them in such places as the Armory Show, New York City’s premier art fair.

“There were human-sized nano rods, sheets, self-assembly, applications in energy, climate change,” says Ozin. “I lost my voice by the end of the week explaining it to all the visitors. We got two main comments: ‘I like the colours’ and ‘What the hell does it all mean?’”

Ozin is currently working with a dozen U of T fourth-year chemical engineering students to design and build a pilot-scale version of his laboratory demonstration ‘solar refinery’ connected to U of T’s physical plant.

“There are different ways of doing this and maybe different methods will be more useful in some parts of the world than others,” says Ozin. “Some places have more wind, some places are sunnier, some have more water,” he says. “Everybody’s pushing their method to valorize CO2 capture and conversion and when the public sees someone holding a gallon of gasoline that’s been pulled out of thin air, that’s going to shake them up.

“If you want to do this on a gigaton-scale, the way that we’re doing it is the way to go.”

How Ozin’s ‘photoreactors’ would create a carbon-neutral cycle:

- Renewable electricity is used to drive current through water, teasing out hydrogen gas that can be used to provide a feed stock for reaction with CO2.

- Renewable energy captures CO2 – for example, from high CO2-emission sources such as power stations, steel and cement factories, or even from dilute CO2 sources in air.

- Once captured into the reactor, sunlight starts to drive the conversion of hydrogen and CO2 when it comes into contact with catalysts made of nano-structured metal oxides and composites with nano-scale metals or other nano-scale metal oxides engineered by Ozin and team.

- Ultra black in colour, the surface of these nano-catalysts absorbs more than 90 per cent of the sunlight spectrum – from ultraviolet to visible to infrared wavelengths – driving thermo- and photochemical reactions that turn CO2 and hydrogen gas into synthetic fuels. “When a black nano-material absorbs light, it gets very hot at the nano-scale, so you get very high local temperatures at the surface of these nano materials,” says Ozin. “So I don’t need fossil fuels to drive the conversion. With just the sun, I can get 500 C at the nano-scale because the heat builds up as vibrational or electronic energy, confined to the surface of the catalyst nanoparticles where the CO2 chemical conversion to synthetic fuels is occurring. That’s photothermal catalysis – it utilizes wavelengths of the incident light across the entire solar spectrum to transform CO2 to synthetic fuels – and it is a process we have patented.”

- Depending on the composition and structure of these catalysts, as well as the reaction conditions – temperature and pressure – the fuel material created can be tailored to produce carbon monoxide, methane or methanol, potentially ready for use in engines, buildings, factories and more.

Ozin says all of this is a way to make the catalysts more efficient. “If we can be half a per cent more efficient than everyone else, that’s a big deal when you’re dealing in hundreds of millions of tons,” he says. “If you can drive it all through sunlight, that’s new. And if you can drive the surface reaction chemistry through light, that’s our contribution.”

Source: University of Toronto, press release, 2017-11-15.