New water-splitting method could open path to hydrogen economy

WSU researchers developed a very simple, five-minute method to create large amounts of a high-quality catalyst

Yuehe Lin (left) and Shaofang Fu, a WSU Ph.D. student, in WSU Lin’s materials engineering lab.

Washington State University researchers have found a way to more efficiently generate hydrogen from water — an important key to making clean energy more viable.

Using inexpensive nickel and iron, the researchers developed a very simple, five-minute method to create large amounts of a high-quality catalyst required for the chemical reaction to split water.

They describe their method in the February issue of the journal Nano Energy.

Energy conversion and storage is a key to the clean energy economy. Because solar and wind sources produce power only intermittently, there is a critical need for ways to store and save the electricity they create. One of the most promising ideas for storing renewable energy is to use the excess electricity generated from renewables to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. Hydrogen has myriad uses in industry and could be used to power hydrogen fuel-cell cars.

Industries have not widely used the water splitting process, however, because of the prohibitive cost of the precious metal catalysts that are required – usually platinum or ruthenium. Many of the methods to split water also require too much energy, or the required catalyst materials break down too quickly.

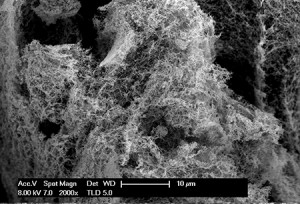

WSU researchers can create large amounts of inexpensive nanofoam catalysts that can facilitate the generation of hydrogen on a large scale by splitting water molecules.

In their work, the researchers, led by professor Yuehe Lin in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, used two abundantly available and cheap metals to create a porous nanofoam that worked better than most catalysts that currently are used, including those made from the precious metals. The catalyst they created looks like a tiny sponge. With its unique atomic structure and many exposed surfaces throughout the material, the nanofoam can catalyze the important reaction with less energy than other catalysts. The catalyst showed very little loss in activity in a 12-hour stability test.

“We took a very simple approach that could be used easily in large-scale production,” said Shaofang Fu, a WSU Ph.D. student who synthesized the catalyst and did most of the activity testing.

The WSU researchers collaborated on the project with researchers at Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

“The advanced materials characterization facility at the national laboratories provided the deep understanding of the composition and structures of the catalysts,” said Junhua Song, another WSU Ph.D. student who worked on the catalyst characterization.

The researchers are now seeking additional support to scale up their work for large-scale testing.

“This is just lab-scale testing, but this is very promising,” said Lin.

The collaborative work was funded by a WSU startup grant and by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Contacts

Yuehe Lin, professor

WSU School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering

phone: 509-335-8523

E-Mail: [email protected]

Source: Washington State University, press release, 2018-02-01.