CO2 utilisation as an alternative to permanent sequestration

According to the International Energy Agency, plans are already underway for over 20 commercial-scale CO2 capturing facilities

If we move away from fossil fuels as a source of carbon, the question arises what should then become our source. Lux Research presents an answer: CO2 utilization. This could fulfil the demand for carbon value chains without relying on fossil-based carbon. But regulatory support will still be required.

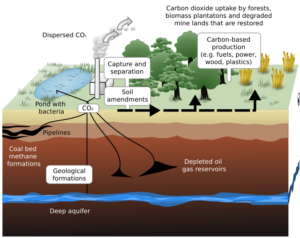

An alternative to sequestration

Lux is a Boston-based advisory company that specializes on sustainable innovation. As they write, CO2 utilization emerges as an alternative pathway to sequestration in the underground. It will also provide us with an opportunity to create value from CO2. They estimate the global CO2 market to become $ 70 billion by 2030, and $ 550 billion by 2040. CO2 could be converted to value-added products in a number of ways: thermochemical, electrochemical or biological.

‘Even in a realized decarbonized economy,’ Lux writes, ‘global energy and chemicals value chains will still need a steady supply of carbon derivatives as feedstocks or otherwise.’ But the carbon source will increasingly become non-fossil. Hence, we will increasingly produce commodity products from CO2 ‘captured from biomass, industrial emissions, and ambient air.’ And according to the International Energy Agency, plans are already underway for over 20 commercial-scale CO2 capturing facilities. For conversion to synthetic fuels, chemicals, and building materials. Moreover, Lux sees opportunities to produce polymers, food and carbon additives from CO2 capture.

Investments on the rise

As Lux notes, from 2021 onwards there is a marked rise in CO2 utilization investments. Before 2021, most investments were in building materials and polymers. But since then, investments diversified. Now, CO2-to-chemicals attract most funds. Most investments take place in the Americas and Europe, where funding by governmental agencies is important.

By sector, CO2 is used for building materials to produce aggregates or in curing wet concrete mix. It can also be used for producing fuels like diesel oil and methane. In the chemicals sector, CO2 is used to produce C1 chemicals like methanol and formic acid. It can also be applied to produce polymers like polycarbonate or polyhydroxy alkanoates. But CO2 can also be used in the food sector. There, it produces single-cell proteins for feed applications. And finally, it can be used to produce materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene.

Building materials and synthetic fuels

CO2 can be used directly in building materials. It can be used to produce aggregates, or be injected directly into wet concrete for curing. While CO2 emissions are unavoidable in cement production (due to the decomposition of limestone), utilization would allow the industry to close its carbon loop. This is a pathway commercially available today. Lux notes that 26 companies develop initiatives in this direction.

CO2 can also be used to produce synthetic fuels; like jet fuels and methane. Some 17 companies are active in this field. But deployment is hampered by the fact that these synthetic fuels are more expensive than fossil fuels. They will therefore have to be supported by regulatory support. Aviation companies are key players in the adoption of the new fuels.

Chemical intermediates

And then, CO2 can also be used for the production of chemical intermediates like CO, methanol and formic acid. However, production of chemicals from CO2 is very energy intensive. Application will require the availability of cheap renewable energy and green hydrogen. In other words, utilization of CO2 in this sector will primarily be a matter of the future. Nevertheless, 34 companies are active in this field.

CO2 can also be the feedstock for polymers like novel polycarbonates, polyurethanes and polyhydroxyalkanoates. These they have to compete with biobased materials. Therefore, most attention is directed towards novel polymers, with a low market share so far. As a consequence, this activity will not have a major impact on carbon abatement.

Food

Alternatively, CO2 can be used as a feedstock to produce proteins for feed or food applications. This is a sector with great promises, but still in an early stage of development. Single cells could in principle produce proteins from CO2. There are many technical challenges; and realization will require a substantial investment. Nevertheless, some major players bet on this avenue.

An opportunity still further removed from application is the production of nanomaterials like graphene. In principle, these materials could capture a lot of CO2. But costs and product quality are major hurdles still to be overcome.

The short term

In sum, building materials, chemicals and synthetic fuels are the most important short-term products. Green hydrogen is a necessary process input for many products. But building materials, polymers and formic acid do not require a hydrogen input and therefore are the prime targets for development. In other sectors, corporations can start off using blue hydrogen, but should then be aware of life cycle emissions.

At the same time, according to Lux, electrochemical technologies are in development that will allow a direct conversion of CO2 and water into chemicals. This could kickstart the production of specialty chemicals. It would allow the chemical sector to continue its operations without reliance on oil and gas. A unique proposition for new business models and revenue streams.

Regulatory support

However, says Lux, such attempts will require supporting regulations. ‘The present regulatory landscape currently favours permanent sequestration over CO2 utilization.’ This might change however as technology develops. Nevertheless, ‘regulatory support will be critical for CO2 utilization products to be cost competitive with their fossil-based counterparts.’

Summing up, CO2 utilization is a fast-emerging alternative to permanent sequestration. It will fulfil the demand for carbon derivatives without relying on fossil-based carbon. We should prioritize the product, says Lux, not the pathway. Selecting the best-fit product will have the bigger impact. And regulatory support is still needed to boost market penetration. The reason: most CO2 utilization products will remain more expensive than their fossil-based counterparts.

Source: Bio Based Press, 2024-11-26.