Scientists make plastic from sugar and carbon dioxide

New BPA-free plastic could potentially replace current polycarbonates in items such as baby bottles and food containers

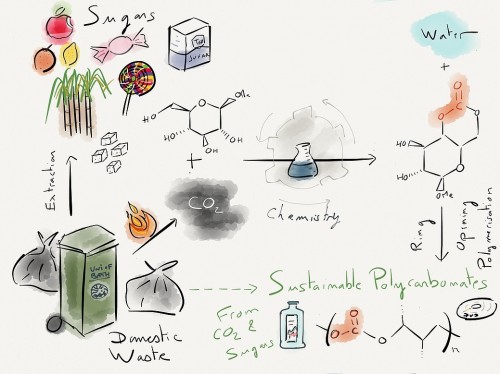

Some biodegradable plastics could in the future be made using sugar and carbon dioxide, replacing unsustainable plastics made from crude oil, following research by scientists from the Centre for Sustainable Chemical Technologies (CSCT) at the University of Bath.

Safer form of polycarbonate plastic

- Polycarbonate is used to make drinks bottles, lenses for glasses and in scratch-resistant coatings for phones, CDs and DVDs

- Current manufacture processes for polycarbonate use BPA (banned from use in baby bottles) and highly toxic phosgene, used as a chemical weapon in World War One

- Bath scientists have made alternative polycarbonates from sugars and carbon dioxide in a new process that also uses low pressures and room temperature, making it cheaper and safer to produce

- This new type of polycarbonate can be biodegraded back into carbon dioxide and sugar using enzymes from soil bacteria

- This new plastic is bio-compatible so could in the future be used for medical implants or as scaffolds for growing replacement organs for transplant.

Polycarbonates from sugars offer a more sustainable alternative to traditional polycarbonate from BPA, however the process uses a highly toxic chemical called phosgene. Now scientists at Bath have developed a much safer, even more sustainable alternative which adds carbon dioxide to the sugar at low pressures and at room temperature.

Biodegradable and bio-compatible

The resulting plastic has similar physical properties to those derived from petrochemicals, being strong, transparent and scratch-resistant. The crucial difference is that they can be degraded back into carbon dioxide and sugar using the enzymes found in soil bacteria.

Plastics from sugar and CO2

Sugar and carbon dioxide are the main ingredients of the new biodegradable plastic (Credit: fcafotodigital)

The new BPA-free plastic could potentially replace current polycarbonates in items such as baby bottles and food containers, and since the plastic is bio-compatible, it could also be used for medical implants or as scaffolds for growing tissues or organs for transplant.

Dr Antoine Buchard, Whorrod Research Fellow in the University’s Department of Chemistry, said: “With an ever-growing population, there is an increasing demand for plastics. This new plastic is a renewable alternative to fossil-fuel based polymers, potentially inexpensive, and, because it is biodegradable, will not contribute to growing ocean and landfill waste.

“Our process uses carbon dioxide instead of the highly toxic chemical phosgene, and produces a plastic that is free from BPA, so not only is the plastic safer, but the manufacture process is cleaner too.”

Using nature for inspiration

Dr Buchard and his team at the Centre for Sustainable Chemical Technologies, published their work in a series of articles in the journals Polymer Chemistry and Macromolecules.

In particular, they used nature as inspiration for the process, using the sugar found in DNA called thymidine as a building block to make a novel polycarbonate plastic with a lot of potential.

PhD student and first author of the articles, Georgina Gregory, explained: “Thymidine is one of the units that makes up DNA. Because it is already present in the body, it means this plastic will be bio-compatible and can be used safely for tissue engineering applications.

“The properties of this new plastic can be fine-tuned by tweaking the chemical structure – for example we can make the plastic positively charged so that cells can stick to it, making it useful as a scaffold for tissue engineering.” Such tissue engineering work has already started in collaboration with Dr Ram Sharma from Chemical Engineering, also part of the CSCT.

Using sugars as renewable alternatives to petrochemicals

The researchers have also looked at using other sugars such as ribose and mannose.

Dr Buchard added: “Chemists have 100 years’ experience with using petrochemicals as a raw material so we need to start again using renewable feedstocks like sugars as a base for synthetic but sustainable materials. It’s early days, but the future looks promising.”

This work was supported by Roger and Sue Whorrod (Fellowship to Dr Buchard), EPSRC (Centre for Doctoral Training in Sustainable Chemical Technologies), University of Bath Alumni Fund and a Royal Society research Grant.

Diagram of the process

The new process converts sugar to plastic using carbon dioxide gas. Credit: Georgina Gregory

Research papers

The research has been published in the following journals:

Georgina L. Gregory, Gabriele Kociok-Köhn and Antoine Buchard “Polymers from sugars and CO2: ring-opening polymerisation and copolymerisation of cyclic carbonates derived from 2-deoxy-D-ribose” DOI: 10.1039/C7PY00236J Polymer Chemistry, 2017, 8, 2093-2104

Georgina L. Gregory, Elizabeth M. Hierons, Gabriele Kociok-Köhn, Ram I. Sharma and Antoine Buchard “CO2-Driven stereochemical inversion of sugars to create thymidine-based polycarbonates by ring-opening polymerisation” DOI: 10.1039/C7PY00118E Polymer Chemistry, 2017, 8, 1714-1721

Georgina L. Gregory, Liliana M. Jenisch, Bethan Charles, Gabriele Kociok-Köhn, and Antoine Buchard “Polymers from Sugars and CO2: Synthesis and Polymerization of a d-Mannose-Based Cyclic Carbonate” DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01492 Macromolecules, 2016, 49, 7165-7169

Source: University of Bath, press release, 2017-06-13.