Diamond provides technical progress

Diamond should help to produce fuels and chemicals from carbon dioxide and light

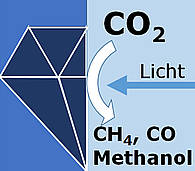

It might be possible with the help of diamond to turn carbon dioxide and sunlight into valuable raw materials, such as the gases methane (CH4) and carbon monoxide (CO) or the alcohol methanol. (Image: Anke Krueger)

This is the goal of a new research consortium receiving around EUR 3.9 million in funding from the European Union. It is coordinated by Professor Anke Krueger at the University of Würzburg.

To date only nature has been able to create organic substances from sunlight and the gas carbon dioxide, which is available in abundance in the Earth’s atmosphere – doing so in a simple water environment. The science world is also keen to master this skill in order to use it to produce fine chemicals or fuels for cars and energy generation, for example. This might work with new technologies based on tailor-made diamond materials.

This development activity will be performed in the new international research consortium DIACAT coordinated by Professor Anke Krueger of the Institute for Organic Chemistry at the University of Würzburg. DIACAT stands for “Diamond materials for the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 to fine chemicals and fuels using visible light”. The European Union (EU) is supplying the consortium with around EUR 3.9 million in funding over the next four years; a good EUR 615,000 of this will go to the University of Würzburg.

The EU approved the project in its Horizon 2020 program. This invited “novel ideas for radically new technologies”. A total of 670 project proposals were submitted, only 24 of which received a funding commitment. DIACAT is the only project among them that is coordinated by an institution in Germany. It starts on 1 July 2015.

Diamond: What makes it so extraordinary

Diamond consists of pure carbon and is a very unique material. It is not just its proverbial hardness and its jewelry qualities that make it a material of the future. “There is so much more to diamond,” explains the Würzburg chemistry professor. Depending on the manufacturing process, you can equip it with other elements, for example, to create a semiconductor from the perfect electrical insulator.

Diamond also possesses exceptional electronic properties. Thanks to these, it is possible to emit electrons from the surface of a diamond electrode with the help of light. These electrons can then be used in water, for example, for chemical reactions with different starting materials.

Goal: To replace UV light with sunlight

Even the mere possibility of producing electrons dissolved in water is already special. “Yet, the high energy of these electrons also enables reactions that would not be at all possible using other semiconductor materials such as silicon, silicon carbide, or gallium arsenide,” explains Anke Krueger. These reactions include returning carbon dioxide to the chemical cycle.

So far, however, the procedure has only worked with ultraviolet light. “Our goal now is to be able to use the visible light of the sun instead and in doing so develop a particularly environmentally friendly technology,” says the chemist. “If we are successful, this will make a major contribution to generating fuels and chemicals in a manner that conserves resources and it may propel technological change.”

DIACAT: The institutions involved

Work toward this demanding goal will be carried out in DIACAT from July 2015 onwards. The project combines the expertise of six universities and research institutes in the field of diamond materials and electrochemistry.

Alongside Anke Krueger’s team at the University of Würzburg, the parties also involved are the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Solid State Physics in Freiburg (Germany), CEA Saclay (France), Oxford University (UK), the University of Uppsala (Sweden), and the Helmholtz Centre Berlin for Materials and Energy (Germany). The final member of the consortium is the German company Ionic Liquids Technologies GmbH (Heilbronn), a specialist in ionic liquids. Administrative support is provided by the agency GABO:mi in Munich.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Anke Krueger, Institute for Organic Chemistry at the University of Würzburg

T +49 (0)931 31-85334, [email protected]

Source: University of Würzburg, press release, 2015-06-30.